Getting Started with 3D Printing for Woodturning

Discover how modern 3D printing technology can revolutionize your woodturning workflow, from custom jigs to precision measurement tools.

Exploring the intersection of traditional woodturning and modern 3D printing technology

Discover how modern 3D printing technology can revolutionize your woodturning workflow, from custom jigs to precision measurement tools.

A journey through the process

There’s something timeless about simple mechanical toys,

and the push puppet is one of my favourites. The way

they collapse with a press of the thumb and spring back

upright as if nothing happened has always seemed magical

to me.

To understand how they worked, I bought an old,

sacrificial one on eBay and carefully took it apart as I

could not find any relevant resources online. A couple

of things stood out right away. The string threading was

clever; it ran across the body and through the plunger

in a way that kept the figure stable while still

allowing it to flop about.

Moreover, inside the base, I found a conical spring

(dia. 15mm – 25mm, 40mm uncompressed) - an essential

piece that gave the puppet its bounce while keeping the

plunger centred thanks to a recess.

The parts themselves were relatively straightforward,

but the scale was challenging. Many of the components

measured only 6–8 mm across, which made handling and

replicating them tricky. After my chuck kissed my

knuckles for the last time, I decided to invest in some

Dome Jaws and get a Record Power SC2 mini chuck which I

would highly recommend for working with small parts.

The string threading starts at the tail and goes down

each hind leg and through the base, it is then threaded

through holes in the sides of the plunger which then

cross in the middle of the plunger, before exiting the

remaining two holes on the opposite sides. This means

the rear left leg is connected to the front right etc.

They then travel back up through the base, and up each

leg until the two strings meet after going through the

body and travel together up the remaining parts of the

neck. These are then tied off in a knot together on the

uppermost section of the neck, before that piece is

glued into a hole at the base of the head.

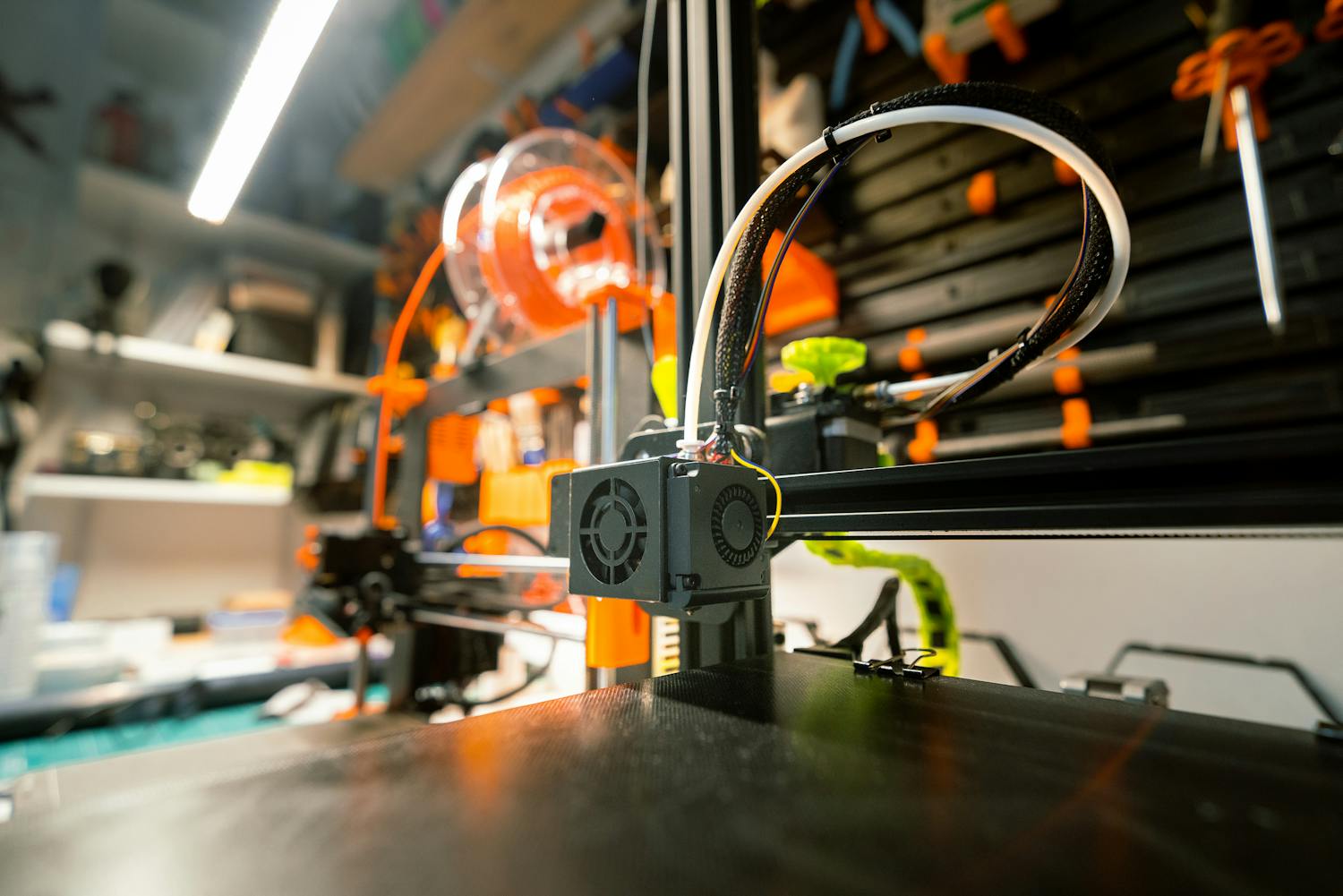

The hardest part was figuring out how to drill precise

holes in the body and head for the wires to thread

through. After a few attempts by hand, I designed an

interchangeable 3D printed guide system that acts as a

bushing to stabilise a cordless drill. The base takes a

dowel that fits in the tool rest hole on the banjo and

has a thumbscrew to swap out guide parts.

I could then create any guides I needed, ranging from

simply horizontal holes of varying diameters to holes

inclined at precise angles of pitch and yaw. More

importantly, I could ensure the entry point of the hole

was at the same point on the wood’s surface, so V-shaped

holes can be made using two guides of +- 15 degrees.

The loop from one back leg to the other can hold a piece of string act as the tail captive when it is pulled back into the tail hole. I used a clamp to compress the spring, so it was slightly recessed in order to achieve the correct tension when tying off the neck knot, which was fiddly business. I would advise doing the assembly over some sort of tray, because one false move sends all the pieces flying as the puppet tends to self-destruct.

In the end, the giraffe came together well, and I added a set of tiny antlers to complete the head. At 2mm at their narrowest point, they’re the smallest I’ve turned and it was a satisfying detail to finish off the project.

A beginner-friendly guide to understanding how 3D printing technology can enhance your woodturning practice with custom tools, jigs, and accessories.

Traditional woodturning relies on specialized tools and

jigs that

can be expensive or hard to find. 3D printing allows you

to create

custom solutions tailored to your specific needs, from

simple

tool holders to adaptors and complex measurement gauges.

Traditional woodturning relies on specialized tools and

jigs that can be expensive or hard to find. 3D printing

allows you to create custom solutions tailored to your

specific needs, from simple chuck key holders to complex

measurement gauges.

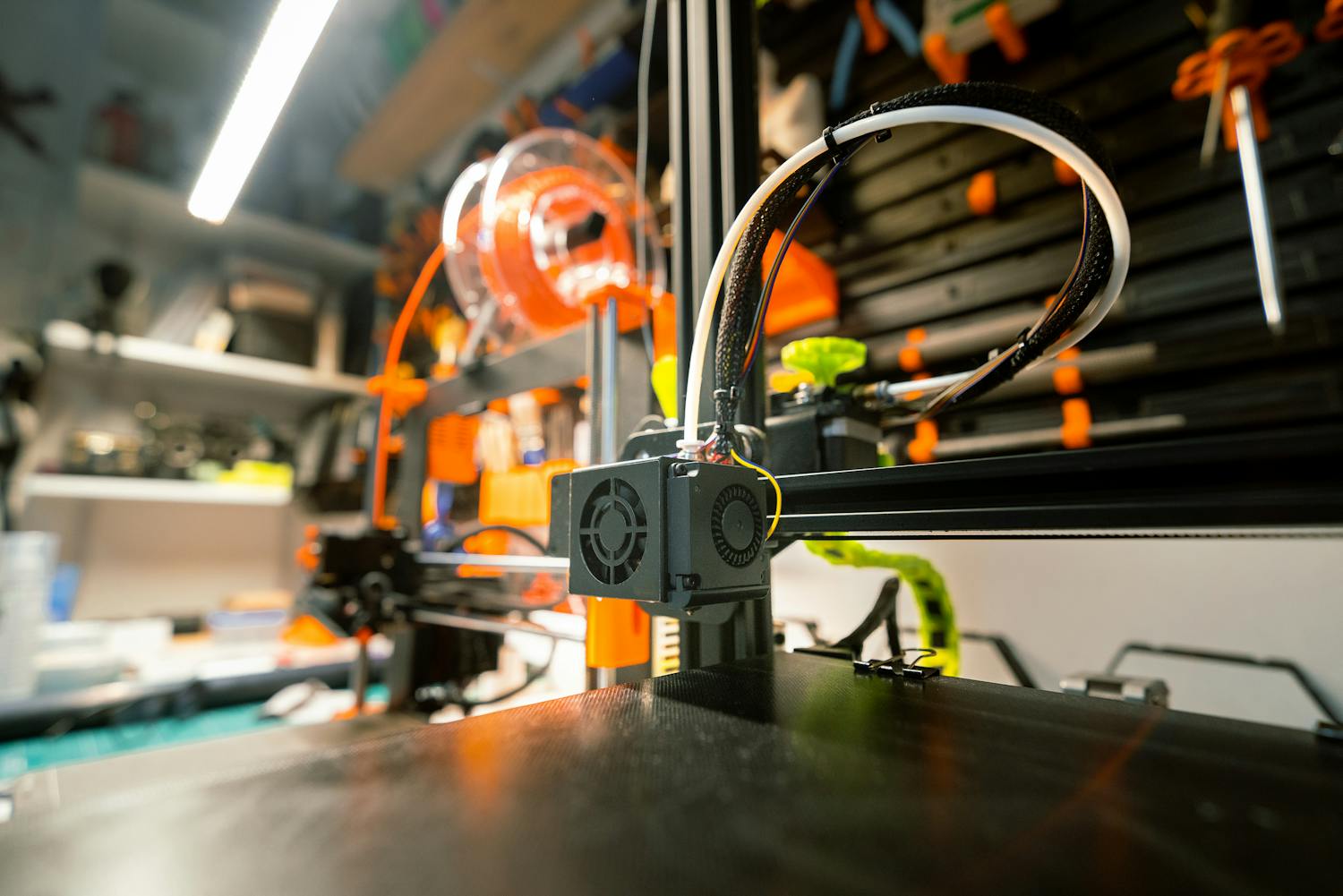

3D printing allows the creation of complex objects without wasting material as it is additive, rather than subtractive like typical machining. The most prevalent type is Fusion Deposition Modelling (FDM) which involves semi-molten plastic being squeezed through a nozzle and deposited like continuous toothpaste by computer controlled motors.

You don't need an expensive printer to begin.

Entry-level FDM

printers can produce durable PLA or PETG parts perfect

for jigs

and guides. Start with printing available designs online

for quick results before learning how to model objects

yourself.

You don't need an expensive printer to begin. Entry-level

FDM printers can produce durable PLA or PETG parts perfect

for jigs and guides. Start with simple designs like

caliper holders or tool rests before moving to more

complex projects.

The orientation of the print will matter as the layers

are weak to shear forces and will tend to separate if

force is applied in the plane of the layers. This is

also why FDM printed parts should not typically be used

in safety critical situations, like for use in custom

chuck jaws, without proper evaluation of the forces

involved.

Centering jigs for mounting stock, diameter gauges for

consistent sizing, sanding guides for uniform finishes,

and custom chuck accessories. These printed tools provide

precision that would otherwise require expensive

commercial solutions.

PLA works well for low-stress jigs and measuring tools. PETG offers better durability for frequently handled items. For parts that need to withstand heat or pressure, consider ABS or nylon. Always test your prints before relying on them in critical applications.

A journey through the process

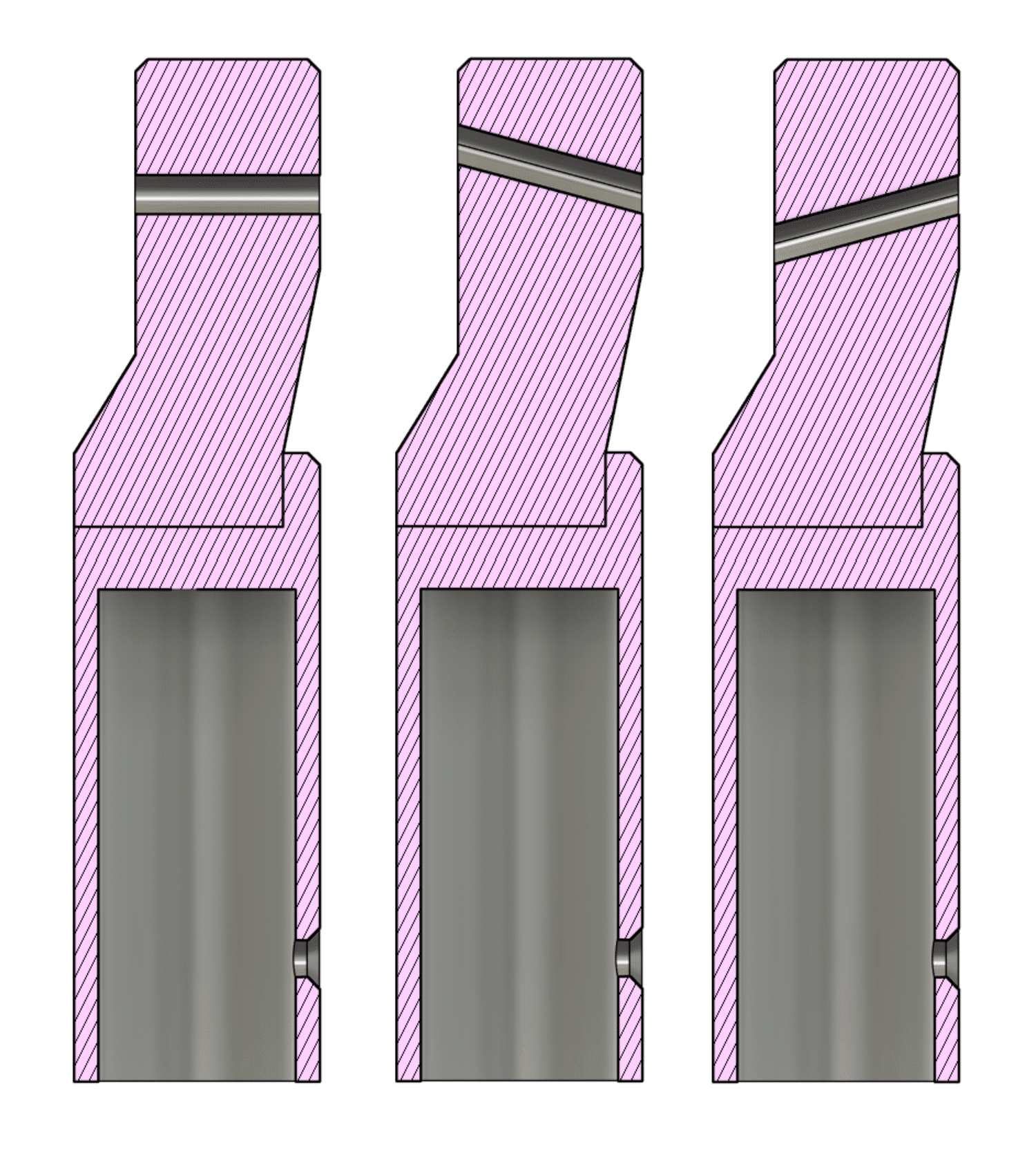

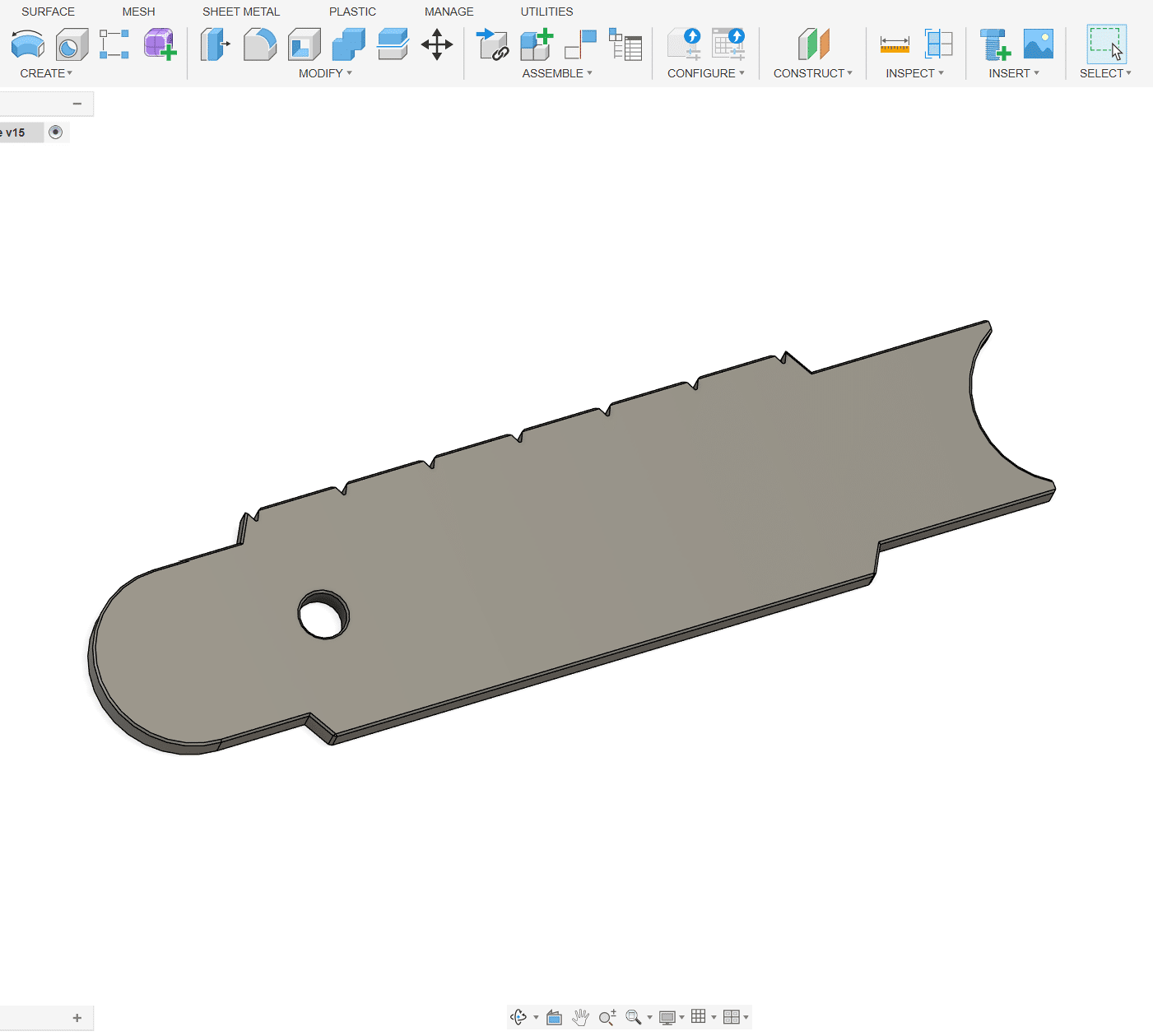

Before I touch any software, I start with paper.

Sketching lets me quickly explore proportions and how

the gauge will interact with beads and coves. I mark out

my ideas for the key features including the ends for

bead and cove fitting, plus the ruler notches for

layout. My initial thoughts for its shape and change as

I iterate through trying to fit all the features into

one compact design.

Once the concept feels solid, I move into a piece of 3D

modelling software, such as Fusion 360. This

gives me the flexibility to iterate quickly and

visualize the tool in 3D before printing.

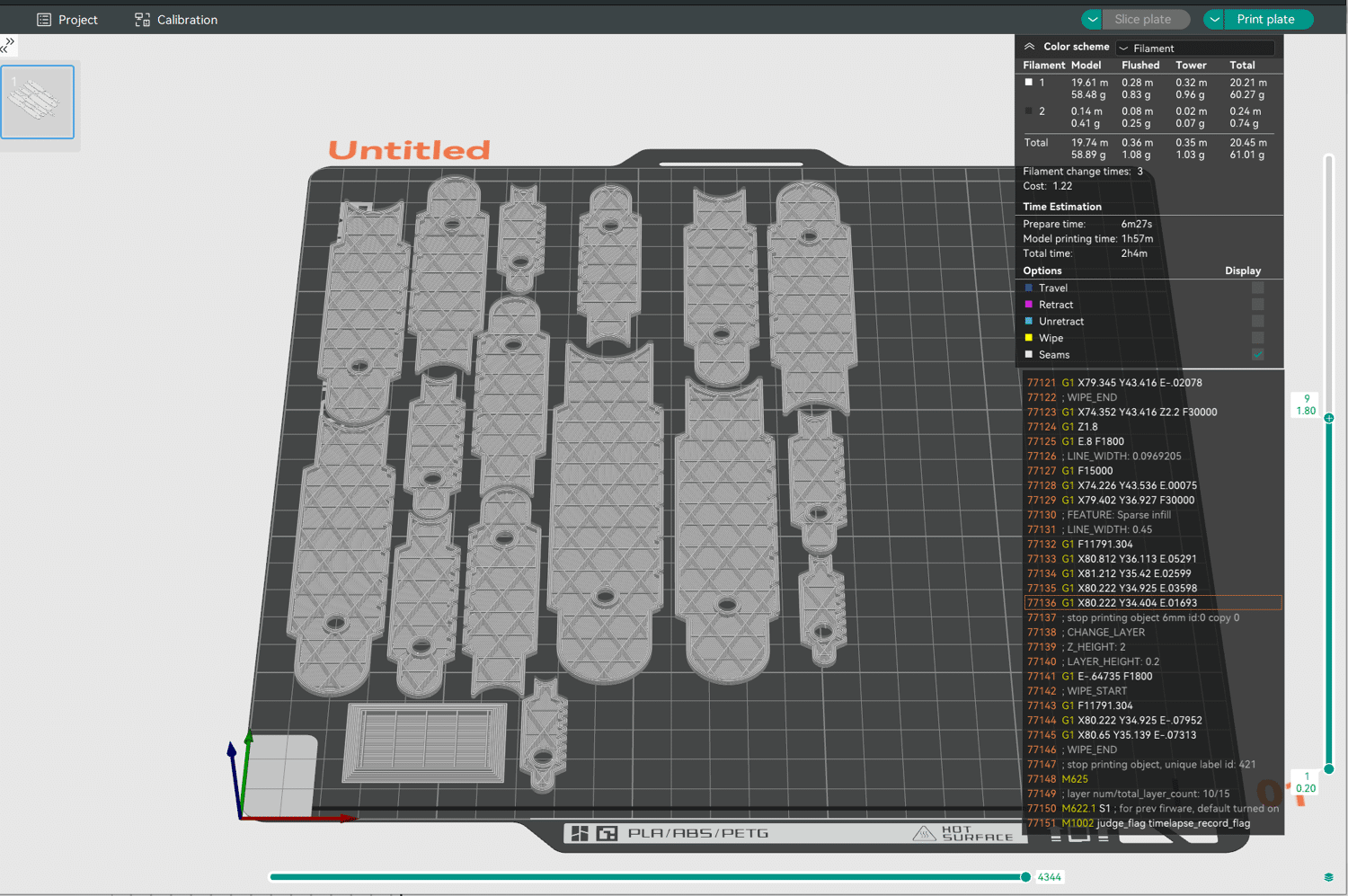

With the model complete, I export it to a slicer, such as Bambu Studio. The slicer software takes all the geometry from the 3D model and converts it into a series of line paths that the nozzle of a 3D printer can follow, effectively creating the set of instructions for the 3D printer for it to make the object. As part of this, the layer height can be adjusted for strength and finish, the model can be split to allow for multi-colour printing, and the density of the finished object can be changed.

Finally, the file is sent to my Bambu Lab P1S. Watching

the design come to life layer by layer is always

satisfying. PLA gives a lightweight but rigid finish,

perfect for repeated use at the lathe.

Through testing the gauges, I can quickly iterate

through several tweaks to make them easy to use

and as feature packed as possible. I rinse and repeat

this process until, along with the help of some testers,

that I am satisfied with the finished product.